Have we reached the end of the line for privatisation?

First it was the banks, now the government is taking over a key rail service. But it may not be enough to reverse the process begun by Thatcher. By Richard Wachman and Tim Webb

- The Observer, Sunday 5 July 2009

- Article history

A train on the National Express east coast mainline service at Kings Cross, the franchise the ?rm has handed back to the government. Photograph: Luke Macgregor/Reuters

Nationalisation used to be a dirty word, but now it's back in vogue. The government's move last week to nationalise the east coast rail franchise comes in the wake of the state's takeover of parts of the UK banking system, all of which has raised fundamental questions about the success of market-driven capitalism.

That may seem strange given that over the past quarter of a century, it has been a one-way street with the transfer of assets from the public to private sector, a process that was the centrepiece of Margaret Thatcher's governments in the 1980s.

For years, no one questioned the prevailing orthodoxy that the running of companies was best left to the market and that managers would perform better if they were answerable to shareholders rather than civil servants.

"The British people have given up on socialism," Thatcher proclaimed on the eve of her first general election victory in May 1979. People forget it today, but Thatcher was very much a creature of her time. She came to power after large sections of the public lost faith in the state's ability to run businesses - the failure of British Leyland, the government-controlled car manufacturer, was a case in point.

According to one veteran of the privatisation of BT in 1984, "Mrs Thatcher embodied a backlash against the state that seemed entirely plausible at that moment. It was said that if companies were left in the public arena, they would be starved of capital and would fail to innovate."

Thatcher's supporters argued then, as they do today, that firms controlled by Whitehall would have to compete for capital with other public sector bodies - for instance, education and the national health service - and that many would sink to the bottom of the pile.

Many privatisations were a roaring success. BT, for example, offered discounted shares to the public during a period when the company was almost universally reviled for its shoddy service and inefficiency.

But since the collapse of the banking system and the state rescue of capitalism itself by government and central banks, the wind is blowing from a different direction.

That doesn't mean that British industry is about to undergo wholesale nationalisation, but many believe that the pendulum has swung too far the other way. Blind faith in global market forces over three decades is viewed as just as short-sighted and dangerous (more so, it seems) as over-dependence on the discredited socialist ideologies that played out in the 1970s.

Mike Kenny at thinktank the IPPR believes that "we shouldn't make a virtue out of either privatisation or nationalisation". He says: "Why does it have to be one or the other? We should look at different ownership models for different industries and decide which one is appropriate on a case-by-case basis."

Richard Reeves at the Demos thinktank says: "We need an agnostic approach to ownership and our thinking needs to be more eclectic and imaginative." Royal Mail, he adds, could become a showcase for employee-share ownership in the same mould as John Lewis, the department store chain.

A senior banker who worked on 1980s privatisations said it was becoming clear that the arguments over privatisation and nationalisation had become "extremely blurred at the edges".

In his view, some things are better produced by government: universal healthcare, defence, justice and policing being the most obvious. But the question of whether the railways had a role in the private sector was open to debate. Other activities were best left to private companies, he says.

But Neil Lawson at Compass, the centre-left pressure group, believes the state must play a much wider role in society than in recent years. He asks: "Are we really saying that we can let the railways fail, the banks collapse or electricity supplies break down? It's poppycock to think that the state should sit on the sidelines."

Jonathan Fenby, of investment research group Trusted Sources, says: "You can close down a company but you cannot close down a rail system. Many industries are so big and important that long-term, central planning is essential."

Different countries have different priorities. In China, for example, social, political and strategic issues play a part in many aspects of public life.

But in Britain, the picture is more complicated, as there is less consensus about what constitutes the public good.

City bankers like Oliver Hemsley at Numis Securities have argued that banks such as RBS should have been allowed to fail and that fitter, leaner rivals such as HSBC and Barclays should have been encouraged to mop up the pieces.

Piers Pottinger, a City public relations executive who steered the privatisations of British Airways and Thames Water, says: "If the state controlled more of our industry, we would be even more indebted as a nation and the public finances would be in a worse state."

It's easy to forget the past, he says. "Although BA today faces severe financial and commercial pressure, for years it was viewed as one of the triumphs of Mrs Thatcher's privatisation programme."

The late Lord King, former head of the airline, was applauded for dramatically improving BA's financial performance and service both prior to privatisation, and after. "It really was the world's favourite airline and everyone loved it. Even the Americans would insist on flying BA, so good was its reputation," says Pottinger.

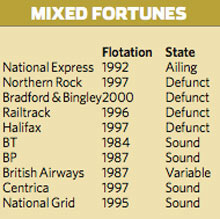

Evaluating BA's success as a private company would seem to depend on where we are in the economic cycle, but it is a mixed record for other firms taken out of public ownership.

Railtrack was effectively nationalised in 2001 amid safety concerns. But there was also a view that its share price was being propped up by an implicit guarantee that the state wouldn't allow the company to fail - whatever the financial mess it got itself into.

The privatisation of British Gas brought choice and competition into the market, driving down prices for a while, but tariffs have surged in tandem with a rising oil price.

Water companies have invested heavily in modernising a crumbling Victorian infrastructure, inherited from the state, but the cost has been rising prices for customers, despite protests from consumer bodies.

The break-up and privatisation of the old central electricity generating board and supply companies made the new groups sitting ducks for larger and - paradoxically -state-controlled enterprises from France and Germany.

Britain's once mighty, nationalised coal industry is a shadow of its former self, hammered by foreign competition and pressure from environmentalists. British Steel has been acquired by Tata of India as manufacturing has shifted east. Banking has fared worst of all. Although former building societies such as Halifax, Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley were owned by their members, rather than the government, their decision to ditch mutuality in favour of stockmarket listings has proved disastrous.

Every major building society that converted in the 1990s has been poleaxed by the credit crunch, prompting government intervention or rescue takeovers by more robust competitors.

True, financial failure isn't the preserve of the private sector, as recent troubles at building societies Dunfermline and West Bromwich have illustrated, but that is where the roots of the current crisis lie.

As the financial crisis rumbles on, however, it is privatisation of the railways, tainted by the humiliating demise of Railtrack, that has proved one of the most controversial.

The government's decision last week to nationalise National Express's east coast rail franchise has reopened the debate over why the train operating companies should remain in private hands. Several other operators are said to be struggling to meet franchise payments, and could suffer the same fate as National Express.

The franchising system has faced criticism for blunting the inventiveness and enterprise that the private sector was expected to bring to the industry.

Many view the system as a cloak to conceal how the department of transport can raise money from train operators to offset the huge bills it faces to fund Network Rail, the infrastructure owner.

Nationalising a major route such as east coast makes it harder for government to shift funding from the taxpayer to the user.

Now the question is whether the role of the private sector in the provision of public services will get bigger or smaller. The answer depends in large part on political persuasion.

Conservatives say the government's borrowing binge and need to balance the books mean that departments and local government will be under pressure to cut costs and raise cash from asset sales. Outsourcing and the use of PFIs will increase, they say.

But in the Labour heartlands, there is quiet satisfaction that business secretary Lord Mandelson has shelved plans to part-privatise Royal Mail. Writing in the Guardian, Labour MP Jon Cruddas said: "For Royal Mail, why not try a not-for-profit enterprise that lets in private-sector management and funding but locks out private shareholders who are only interested in the profits they can squeeze out of postal deliveries?"

But David Freud, the City author and former SG Warburg banker, thinks that keeping Royal Mail in the public sector is a mistake. "Look at Holland and Germany, which have privatised their mail businesses and now have leading positions in international logistics," he says.

No one can know for sure who will win the debate about the future shape of capitalism that is now raging. But in a recent defence of finance capitalism, Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales conceded that free markets are vulnerable to attack in downturns because they rest on fragile foundations, depending on the goodwill of politicians for their existence.

The extent of their vulnerability, though, will depend on the severity of the downturn and the political persuasion of the next government.

But no one should be under any illusion that the world has changed a great deal since Margaret Thatcher left Downing Street 20 years ago. Nationalisation, raising taxes and Keynesian economics are back in fashion. And many of the virtues that she claimed for the market place have been shattered by the greed and stupidity of bankers, and the short-sightedness of politicians on both sides of the divide.

From money-pot to millstone: how company pensions have helped and hindered

Pensions have always played a key role in major privatisations. At the time of the sale of British Telecom, thousands of unwanted staff were offered early retirement rather than redundancy by ministers who saw the company pension scheme as a no-cost solution to cutting jobs. It was a trick repeated many times during the 1980s as government-owned businesses were slimmed down in readiness for sale to the private sector.

In the 1990s, UK companies saw their schemes as a huge cash reserve and many firms, including illustrious names like Unilever, not only offered early retirement but also doubled their profits with cash diverted from the pension scheme.

Since the stockmarket slump of 2003, which coincided with stricter accounting measures of pension fund deficits and more realistic views of life expectancy, pension schemes, far from facilitating cost-cutting and boosting profits, have become a huge drain on company finances. In the last three years, the UK's major listed employers have spent more than £15bn topping them up in a desperate bid to close deficits. Earlier this year, the pensions regulator insisted employers rank their final salary pension schemes ahead of dividends to shareholders when they consider what to do with extra cash.

Last week, pension advisory firm Mercer went further and said that the scheme trustees who oversee occupational funds should be at the top table during any restructuring or sale of the business. The consultancy, which advises many FTSE 100 companies, said banks must recognise the new economic reality and "give greater consideration to the demands of trustees of defined benefit pension schemes when negotiating terms with companies seeking restructuring and refinancing".

In a 180-degree turnaround from the position widely held in the 1980s, Mercer continued: "The pension scheme is a major stakeholder in the wider financial position of the sponsoring company. As significant players, scheme trustees should be automatically invited to the negotiating table... These negotiations might impact upon the employer covenant, and the employer's obligations to the pension scheme should be factored in to avoid complications and disputes down the line."

For companies like BT and British Airways, both privatised in the 1980s, statements like this spell nothing but trouble. To say directors cannot move without consulting pension trustees is often to put an effective block on progress: although the regulator and trustees would deny it, City analysts are clear that companies locked in a titanic struggle over their pension scheme are best avoided.

Independent analyst John Ralfe has campaigned for privatised businesses to offer a realistic view of their pension liabilities. He believes the huge deficits in the BT scheme and those at other major former public-sector employers would be even bigger if they updated their life expectancy predictions and cut back on their optimistic view of investment returns to the fund.

He says: "Many of the companies with the biggest pension problems are former nationalised businesses, partly because they employed a lot of people, with relatively generous pensions. When each company was privatised, no one properly thought about pensions as a potential problem. By transferring this problem to shareholders, the taxpayer got a better deal from privatisations than it appears."

The rail companies avoided taking over the management of the £16bn rail pension scheme when the Major government created a myriad of franchises in 1993: instead, there is a scheme to which every train operator must contribute while it holds a franchise. Unlike BT and British Airways, which have switched new employees into cheaper plans minus the guarantees offered by final salary schemes, railway workers have successfully protected rights for new and existing staff.

To an increasing number of analysts, the demands of workers with final-salary benefits are not only denying investors their slice of the profit cake, but also stifling investment in the business and the scope for employers to reward new employees. British Airways is typical in contributing the equivalent of 25% to 50% of workers' salaries into its pension scheme to keep pace with the growing costs of maintaining a final-salary guarantee. Personnel directors have reported that they can spend more than half their time dealing with issues related to a defined-benefit scheme, even when it only affects a third or less of the workforce.

To this extent, the tail is wagging the dog. For the 2.7 million workers still paying into guaranteed pensions, another year of falling sales and profits could prove crucial.

Phillip Inman

Adonis: man of steel

Few could have expected the political career of Andrew Adonis to outlive that of Tony Blair.

The former policy adviser and junior education minister was behind some of Blair's most contentious policies, including university tuition fees and academy schools, making him deeply unpopular with Labour backbenchers. He also railed against comprehensives, which he said had "destroyed many excellent schools without improving the rest". Some viewed him as a kind of Conservative fifth columnist.

When Blair stepped down, it was anticipated that Adonis would soon be looking for other work - he had previously been an academic and a journalist for the Financial Times and the Observer. Instead, he re-emerged last month as secretary of state for transport in the reshuffle regarded by many as Gordon Brown's last throw of the dice, and last week was thrust to centre stage.

Adonis found himself in a confrontation with National Express, standing firm against demands that it be allowed to renegotiate its £1.4bn contract to run the east coast main line from London to Edinburgh. By taking the line, at least temporarily, back into public management he may have even won over a few critics from among his own party.

Stephen Glaister, professor of transport and infrastructure at Imperial College London, says: "Adonis is doing exactly the right thing. There has been a tendency within government to be tripped into renegotiating contracts and letting failing contractors off the hook."

Conor Ryan, who was a special adviser to David Blunkett and worked alongside Adonis in the education department, is not surprised to see him displaying backbone: "If he is sure something is right and needs to happen, he is quite prepared to be steely."

Adonis, 46, graduated with a first from Oxford. He had reason to be passionate about education. His mother left home when he was three and Adonis was put into care, visiting his father, a Greek Cypriot waiter who lived in a council flat in Camden, north London, at weekends. He was awarded a local authority grant to attend boarding school before going on to Keble College at Oxford to read modern history.

Made a peer by Blair in 2005, Adonis became a minister without facing an election, providing critics with further ammunition. But Ryan says he has won respect within the Brown camp: "What makes him unusual is he is very much concerned with the detail of delivery. He knows that you can't just set out a policy and then leave it to the system."

Said to have an encyclopedic knowledge of the rail network, Adonis embarked in May on a week-long tour of Britain's stations, which he described as an "exercise in total station immersion". The low point, he said, was "my inability to buy so much as a cup of tea at Southampton Central at 8pm on a cold Tuesday evening".

David Teather

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7Qq01tC0lU

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gt7cvcg22n0

No comments:

Post a Comment