House of Death Informant, Facing D-Day in Court, Pens Letter from Prison

Narco News Obtains Ramirez Peyro Letter on Eve of Hearing that Could Bring a Death Sentence Called Deportation

By Bill Conroy

Special to The Narco News Bulletin

August 18, 2008

In recent months, Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, has become the killing fields of the drug war, with an average of about 100 murders a month so far this year — 780 as of yesterday by one count.

But like most figures in the drug war, there is nothing certain about that number. It might well be higher, with more bodies out there, hidden, still waiting to be counted.

The paranoia that exists in this Mexican city across the border from El Paso, Texas, is hard to describe, or at least it has taken me several months to internalize since visiting Juarez last spring.

A recent article penned by drug-war journalist Chuck Bowden for GQ Magazine puts it this way:

The violence is everywhere. It has no apparent and simple source. It is like the dust in the air, part of life itself.

In other words, the old script of “cartels” battling it out over turf no longer explains fully the carnage in Juarez. Bowden’s article has helped me to see things a bit clearer. He is right, I think; there are many causes for the extreme bloodshed in Juarez in recent months.

But at its core is the drug war and the breakdown of civil society that it eventually brings to all who are sucked into its void. In that world where the entire city of Juarez now exists, there are only hunters and prey; no one is exempt from that rule of survival.

Shattering Society

The House of Death murders took place more than four years ago, before Mexican President Felipe Calderon escalated the drug war by ordering the military into Juarez, before the U.S. government authorized millions of dollars to further arm the hunters via Plan Mexico and before the narco-traffickers lost control of the killing fields.

But even four years ago, as a U.S. government informant assisted narco-traffickers and Mexican cops in carrying out the torture and vicious murders of a dozen people, the signs of the break down of civil society — on both sides of the border — were all there in front of us.

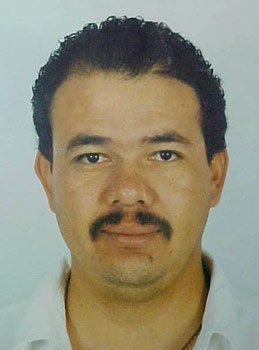

Mug shot of the informant Guillermo Ramirez Peyro |

The prey, including at least one U.S. legal resident, were eventually found buried in the backyard of the House of Death at 3633 Parsioneros — a dead-end street in a seemingly sedate residential neighborhood in Juarez.

The murders were carried out between August 2003 and mid-January 2004. After participating in the first murder, the informant Ramirez was authorized by his ICE handlers, with the approval of high-level officials at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS, which oversees ICE) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), to continue on his mission — resulting in at least 11 more murders and the near assassination of a DEA agent and his family.

This all played out despite the fact that the U.S. Attorney overseeing the case, Johnny Sutton in San Antonio (a friend of President Bush), had enough evidence to close out the investigation against Santillan several months prior to the first House of Death murder, but instead chose to allow the informant to continue his bloody work. That was the first sign that civil society on the U.S. side of the border was beginning to crack.

And when a lone DEA commander, Sandalio Gonzalez, in El Paso sought to expose the U.S. government’s complicity in the needless carnage, via a memo drafted in February 2004, rather than investigate the charges, U.S. Attorney Sutton chose instead to use his pull within DOJ to retaliate against the whistleblower and assure his message was silenced. And to this day, the cover-up continues — assuring that the crack in civil society will continue to expand.

The DHS is now seeking to deport the informant Ramirez, who claims that once returned to Mexico, the narco-traffickers he betrayed will murder him — with the help of Mexican government officials and law enforcers who are employed by those same narco-traffickers.

Sandy Gonzalez, former DEA Special Agent in Charge in El Paso |

The tortured course of Ramirez’ immigration case appears to be yet another example of the breakdown in civil society on this side of the border. In this case, our own government, playing the role of the hunter, is acting under the camouflage of law to essentially assist in the murder of the prey (the informant Ramirez).

Message from the Void

It is in that context that Narco News wishes to share with you, kind readers, a letter from the informant, written in pencil a few months ago in his prison cell, that details, from his point of view, the events leading up to the House of Death murders. The letter was written in Spanish, and translated by Narco News into English — though the original letter can be found at this link for those who prefer to read it in Spanish.

Ramirez’ prison missive recounts the initial stages of his efforts to infiltrate the Santillan narco-trafficking cell in Juarez. What is striking in his recalling of these events is his description of the clear complicity of U.S. law enforcers in either directly assisting Juarez narco-traffickers, or turning a blind eye to the bloodshed — and, at times, even the drug smuggling — in their efforts to make a big case. (However, it is important to bear in mind that the prison letter recently obtained by Narco News is only Ramirez’ version of events.)

Santillan was eventually arrested by U.S. law enforcers, but never stood trial. Instead, U.S. Attorney Sutton cut a plea deal with Santillan in 2005 (just prior to DHS initiating deportation proceedings against Ramirez). As part of the deal, Sutton agreed to drop murder charges against Santillan in exchange for Santillan copping to narco-trafficking-related charges — and accepting a long stint in federal prison.

The deal assured that the U.S. government’s dirty laundry in this case would never be exposed to the sunshine of a public trial.

The informant Ramirez grew up in Mexico, the son of professional parents who worked as civil engineers. After taking a stab at college, he went to work in the late 1990s as a federal highway patrol officer in the state of Guerrero in southern Mexico for about a year before he was fired because he had problems getting along with his boss.

Ramirez then moved into the drug business full-time. Ramirez says that was a natural career move, since he had already made numerous connections in that world while working as a cop. He managed the distribution of drug shipments for a narco-trafficker based in Guadalajara, Mexico, (coordinating the movement of drugs from Colombia into Mexico) for a while and eventually made his way to Juarez to begin his work for Santillan.

House of Death in Juarez |

On that score, Bowden’s insight into the nature of truth in the drug war is worth sharing. Again, from his recent GQ article:

In Juarez there are many versions of every event — but everyone agrees on what happened after …

In the case of the House of Death, “what happened after” is the fact that 12 bodies, contorted in the grizzly poses of the torture they endured just prior to death, were found buried like garbage in the backyard of a middle-class home in Juarez.

The Prison Letter

NOTE: Information in [brackets] is context provided by Narco News. The letter only references a year once (2000), so the timeframe of these events can only be estimated, though they all appear to have played out between 2000 and 2002 based on month and seasonal references in the letter. The first murder at the House of Death — in which Ramirez was a participant — occurred in early August 2003.

... While I was back home [in Mexico, in late 2000], I found out that some engineer [a narco-trafficker] had left me a number to get in touch with him. I called him and it was Heriberto Santillan, a person I had met a couple of years before. At that time he mentioned that he had just served, I think, an eight-year sentence in jail in Torreon, Coahuila, that they had caught him with some little marijuana plants that he was taking care of for Amado Carrillo, but that the army captain that had arranged things with the superiors couldn’t fix it with the boss, who was new or something like that. [Amado Carrillo, presumed to have died after getting plastic surgery in 1997, led the “Juarez Cartel,” which has since fallen under the shadow of his brother, Vicente]

So they arrested him [Santillan] and he did his time. And that he had made good contacts in jail with bosses, besides the ones he already knew. From the time he was a young man he moved around Sinaloa, Durango, Chihuahua, Coahuila y Tamaulipas. He even said to me that we should go to Monterrey with a buddy of his that had been in jail with him and was an ex-comandante of the federal court [a magistrate], that he was PESADO [burdened, weary] and maybe we could pick up some weapons. … So we did it, but we didn’t get any weapons. And about a month later, I got sick and I was out of circulation for about six months, so I didn’t hear much about Santillan and so I called him [when I got back on my feet].

We met early one morning. We went to the plaza to get our boots shined. Santillan now looked like he was addicted to cocaine. He now lived in a better neighborhood about three blocks from my house. He had something like four model year cars, two houses, a farm, lots of jewelry. I think he even talked like a snob [tipo fresón]. In the end, he asked me that if we could go back to Juarez together at the beginning of the year, that we would go in his car. I told him yes, Happy Holidays, and to call me when he knew the exact date.

I don’t remember what day, but it was sometime between the fifth and the eighth of January that we took off for Juarez and the whole way Santillan talked about his adventures during the time that we hadn’t seen one another, and what stood out was that he had reached a high level among the group of operatives of the Juarez Cartel, which is led by Vicente Carrillo Fuentes. He explained to me that the group of operatives was led by Arturo Hernandez Hernandez, alias “El Chucky.” And that his buddy, the one we had been to see in Monterrey, was a friend of El Chucky, and how the higher-ups had settled around Torreon, Gomez Palacio, y Lerdo, so he and his buddy had the perfect set-up.

Mug shot of Amado Carrillo FuentesHe [Santillan] told me about the friends he was hanging around with when I met him (Elias and El Guero, who were also acquaintances of mine and were the ones who controlled the drugs around there). Well they had fallen out of favor with the boss and they had been ordered out of the city, but instead of doing that, they had gotten into more trouble with some of Vicente’s [Carrillo Fuentes, the supposed major domo of the Juarez Cartel] relatives since they had killed one of the boss’s cousins.

And moreover, they picked up a guy who had a heart condition who died from sheer fright. The problem is that he [El Guero] owed a shipment to the boss, so they told Santillan to bring him to one of the safe houses. So he [Santillan] invited him [El Guero] to something, and when they got there, the boss appeared, gun in hand, and El Guero only cried out once before he died.

And they sent Elias the message for the last time that he needed to get out of there or they would send him to see El Guero. I think Santillan thought I looked funny, because he said: “Yes, we were friends, but here in the Mafia, if they tell you to fuck somebody over, you do it, and if not, they’ll fuck you over instead, and then they’ll also fuck him anyway.”

Snitching on Santillan

He [Santillan] also told me that there was a guy who was from Caborca, I think it was, who had gotten behind on some payments and moreover had gotten cocky. So they had cut off his head and thrown the body in a canal, and that it had been in the newspaper; that they had also killed one of his brothers, and that he had another brother who worked for the … police in Cuidad Juarez and he [the brother] had asked his commander if he could go investigate what happened to his brothers. And that after hearing the story, the commander ordered him [the surviving brother] tied up and they killed him, since the commander is Santillan’s nephew and Santillan was the one who got him the job so that he could carry out the work of the cartel. [Santillan’s nephew is Miguel Loya, who served as a commander with the Mexican state police in Juarez and was a key figure in the House of Death murders.]

He [Santillan] also told me that the ones from the DEA were also on the payroll and that when the operatives [law enforcement] were coming, they warned them ahead of time so they could leave the area for a while. So that when the operatives come, there is nothing happening and they leave empty-handed like they did at Amado’s sister’s wedding. [It is not clear where these allegedly corrupt DEA agents worked, or if Ramirez Peyro’s claims even have merit. To date, there is no evidence that DEA’s agents in Juarez were on the payroll of narco-traffickers; however, a memo drafted by a Department of Justice attorney in 2004, called the Kent Memo, does allege that DEA agents in Bogota Colombia and Washington, D.C., have been compromised by narco-traffickers.]

He [Santillan] also said that they had told them about the crybabies [snitches] and that they had already killed two of them from Torreon; and he told me that a lady who used to clean one of the houses … and that they sent a guy to her house dressed like a worker from the water company, and when the lady opened the door he shot her.

He [Santillan] also told me that he had traveled all over the country orchestrating and escorting the cocaine shipments that were coming from South America.

I asked him that since he made good money and had his farm and all, if he was thinking of retiring. He said no — once in the Mafia, there was no way out, since they thought it would be considered treason.

I really had nothing to say. I only told him about my illness and that in Juarez I was only involved with the ones who brought [ONAPAFOS/illegal] cars as an intermediary or a packer. Santillan asked me to help him get smugglers, packers, grocers/sellers [BODEGUEROS], truck drivers, really to hire everybody necessary [for narco-trafficking]. He told me he already had everybody, but it was always good to have more options.

So then in Juarez he agreed to call me, and I went to El Paso to talk to [Raul] Bencomo [the U.S. Customs, now ICE, agent who recruited and initially handled Ramirez Peyro as a U.S. government informant]. I asked him if there was anyone in his office who would be interested in what we were working on with Santillan, that he should talk to his bosses, and that they should be more competent, because in the cases I’d done before, they had left me with a lot of problems, and that this was the big league so they had to be smarter. And I told him everything Santillan had told me on the way.

Mug shot of Heriberto Santillan TabaresAfter talking with his superiors, Bencomo told me that, yes, they were interested in the Santillan case, and that they would do everything they could so I wouldn’t get burned again. I told him that the best thing for the moment would be to begin to hire truckers because that way we could take the drugs somewhere else and give them [U.S. law enforcement] more time to seize them, and that way they wouldn’t suspect me. I also reminded him, “No DEA,” given the things that Santillan had said.

At that same time, they [some of Ramirez Peyro’s other Juarez drug-smuggler contacts] offered me a crossing with a corrupt [U.S. Customs] inspector, which I discussed with Bencomo. And he told me that he was again interested that I become involved in that case too.

Two Bosses

At this point, I went from appointment to appointment between Bencomo and Santillan who, because they were so busy, had the habit of keeping me waiting, sometimes for hours, or looking for truckers or smugglers that normally had at least three intermediaries, which made the process extra slow and tedious and most of the time ended up being just lies. So with enormous patience and telling my “bosses” (Bencomo and Santillan) over and over not to lose faith in me, I began to find the road to the disaster.

In these numerous meetings with Santillan, I got to know members of the organization and other Santillan collaborators. For example, I saw his nephew Commander Loya hand over, or rather throw, 100 kilos of cocaine in bundles of 10 kilos on the sidewalk and sneer ironically, “Who cares what those sons of bitches know.” Referring to the neighbors that could see everything that was happening.

… Around that time I told Santillan about my friendship with the corrupt inspector, and he told me we’d get [that he wanted to get] his border-crossing card back, that the Border Patrol had taken it because they caught him taking his girlfriend who had gone through Santa Teresa. I told Bencomo, and he told me that he could only get him [Santillan] a permit like mine, and so it was done. The thing was that when we showed the permit to the [U.S. Customs] inspector that interviewed us [while crossing the border into El Paso] he subtly asked Santillan, “Where did you get this permit?” To which I prompted him “from the office on Hawkins.”

And then the brilliant inspector asked him, “Why did they give this to you? Do you work with the US government?” To which Santillan, who was already red as a tomato, said, “No,” and I, who was a white as paper, prompted him to say, “Yes.”

In the end the idiot finally let us go and all I could say was I didn’t know what sort of illegal dealings my corrupt friend [the U.S. Customs Inspector] had arranged, but he had told me that if the inspectors got rough that I should tell them to call him, since those permits were only given out for official use. Thank God Santillan was far from suspicious and decided that to avoid a situation, it would be better for him to tell me when he wanted to cross so that I could go with him.

Corruption at the Bridge

Around that time, Bencomo had arranged for an undercover agent who was a trucker, and I introduced him to Santillan. And he even gave him $1000 or $2000 so as to seal the deal, but nothing ever came of it. Also at that time, the deal with the people who had the corrupt inspector took shape, and taking advantage of Santillan’s absence, I concentrated on the case of the corrupt inspector.

There were three intermediaries in this case, the nephew of the inspector’s wife and two of his friends. When my associate, his brother, the three intermediaries I mentioned and I finally met, they explained to me that they had worked with the inspector for more than a year, but the ones who provided the [drug] loaded cars, el Negro y El, had thrown them off [messed things up] and had threatened the inspector so that he would not continue to work with them.

So they wanted me (by this time it was already known that I was with the cartel) to provide the loaded cars and to cover them. In exchange, they would work only for me. I accepted their offer, but I asked for a detailed explanation of the modus operandum, which was not so simple, but went more or less like this:

Upon his arrival at work, the [U.S. Customs] inspector would receive his schedule where he would see when he would be at the different stands [at one of the border bridges at Juarez/El Paso] where the cars came through…. And since they switch off every thirty minutes, he could use one of the beepers that were already programmed to type in and send the messages without needing to use an operator or telephone line.

He [the corrupt inspector] sent the schedule to the nephew specifying at what time and on what line he would be working. In that way, he was the first contingency and would send us the schedule, or as we called it “invitation,” since we were the guests. The second contingency was that there was rarely a line more than twenty minutes on the Libre Bridge [the Bridge of the Americas crossing], which is the one we worked.

But we ended up getting the best payoff of time by sending one of the nephew’s friends to the stand of the inspector in question, and so he, upon seeing him, knew that he had to speed the line up until the loaded car(s) had passed through.

The third contingency was that we physically saw the inspector working in the stand. The fourth contingency was that Customs would bring the dogs. Since the whole thing was so bold, the car would be perfumed. That was in theory.

So after I explained it to Bencomo and his companions [at U.S. Customs, or ICE], they told me to see if it was true that there was a corrupt inspector (I.C.), so I took on the job of finding someone who would send a shipment, which wasn’t easy, especially after the bitter experience we’d had [in past informant dealings] with Bencomo and his people.

It had to be God’s hand that at the beginning of March I had five different groups of criminals available to participate in the crossing with the I.C.

But first they all wanted to see someone get through. Every one of those prospective drivers wanted to see someone go through before they would go themselves. So I explained the situation to Bencomo, and he told me to do everything possible to obtain the first one and identify the I.C. I told him then I would have to drive. He said that if something went wrong that I should tell them [the U.S. Customs inspectors at the bridge] to call him, and that if it went well not to say that I drove.

We agreed that it was the only way to prove the truth, to find out who the inspector was and get the others to work. If it went well, I would have extra drivers and I wouldn’t have to get involved, but if it went badly, I would prefer to go to jail than stay in Juarez and have to explain myself and/or pay with my hide.

Miguel Loya, a Mexican state police commander at the time of the House of DeathSo I convinced my associates and the owners of the (MERCA- merchandise) that we would outfit my car for the job and that we would load it with everything we needed to be able to pay the I.C., with the understanding that it would demonstrate our readiness to begin working, and then the earnings would be forthcoming.

That’s how we did it, and one day at 6:00 AM, with a slew of onlookers, among them [Santillan’s nephew, Mexican state police commander] Captain Loya, his agents, prospective clients and drivers, intermediaries and my associates, I took the first car across, which I left at the McDonald’s on La Paisano [in El Paso]. I returned to Juarez and after about four hours, we determined that the operation had been a success, so I let my associates be in charge of collecting the money to give to the I.C. and to the others who went to prepare their cars.

Since I was the hero, I said I was going to take a rest and that we would meet up at nightfall to see how many cars were ready to be assigned drivers and find a house where we’d wait for our invitation.

That said, instead of resting, I went to see Bencomo and his people, who upon hearing the story showed me some photos. In one of them, I saw the I.C.’s … face.

Bending the Rules

So we finally had a case, but since I had to become involved in the activities in Mexico, [ICE El Paso Supervisor] Curtis Compton said that they would have to wait for Washington [D.C.] to get permission to use me as an operative/informant. [It is worth noting, based on Ramirez’ account, that he appears to have already been operating as a U.S. informant in Mexico prior to official Washington approval.] That for the moment we couldn’t do anything, just that I should take note of everything that was sent through. To which I made him see that it wasn’t just taking notes, that as he well knew the operation was very complicated and involved various criminal groups who were synchronized down to the slightest detail by an attendant, and that it would be impossible for me to just stand to the side now that I was the Ray Coniff [a player]. Everything would fall apart if I distanced myself, with the additional risk of my associates undermining the relationship with the I.C., since we knew they were lazy and not very bright, their ethereal credibility besides.

So we agreed that I would keep coordinating everything so that when the permission came from Washington we would have everything on a silver platter.

At the same time as the business with the I.C., I keep meeting with Santillan because he kept asking me to go. And he talked with some of my associates and me about how things were done in the cartel.

And he [Santillan] even told us to be aware of anyone selling cocaine or saying that they had connections with the cartel, to investigate it immediately and if necessary take appropriate action. And that we should be ready to support the operations that would soon take place — that being blowing up the houses of people [murder] who in some way had affected the cartel’s interests. We exchanged phone numbers with his nephew, Commandant Loya, and since Santillan was not always in Juarez, anything that came up we would take care of directly amongst ourselves. As always, I told all this to the OIUSC [Office of Investigation, U.S. Customs — which has since become ICE, or U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement].

Road Trip

Among the great number of hoodlums that ran with us, there was one bald guy known as “El Gato Madrid” that had some good times, but fell out of favor. He was always chasing women (or deceiving people) with Miguel Angel Sanches, an architect who said that he also had an I.C. [corrupt U.S. Customs Inspector], to which I asked them to set up a time when he could have an interview with him or his representative and to be sure to tell him that we would give him work. Or in the meantime, if they wanted to drive with the I.C. that we were working with, I paid $2000 per trip, and given their situation, they didn’t see anything wrong with that. So El Gato perked up and DIO UN PAR DE BRINCOS [did a couple of drug-smuggling runs], which helped him pay not only his back rent but several months ahead and add to his wardrobe.

Holy Week came and I excused myself from my associates [in Juarez] and from US Customs because I was going with Santillan back to my hometown [Durango, Mexico], since he had to take some money he had gotten together (from cocaine sales) and he asked me to go with him.

… So I got the vehicle and I picked him [Santillan] up from one of the houses where it was certain that, like my compadre Santillan, some of the high command of the cartel at the local and national levels were. From there we left, a vehicle in front, Santillan and I with the money, and his compadre bringing us the rear [following in their vehicle].

After the first stop for gas, Santillan smilingly said to me, “Man, my compadre wanted to kill you! He had confused you with the brother of a jerk we killed last year, and just a little while ago he asked me why I brought you along and if we were going to throw you out on the road. And I [Santillan] told him, “No, compadre, this is Lalo, the one that I introduced you to in Saltillo. …” All the rest of the trip was without incident and mission accomplished. I went on with my family business and returned to Juarez to undo all the damage that had been done in my absence.

Hunters and Prey

In reality there were two drug-smuggling runs [BRINCOS] during my vacation, one without incident, but with the second one the synchronization failed. They were very late in letting the driver through [the bridge back in El Paso], which resulted in him arriving at the guardhouse when the I.C. wasn’t there. But it was lucky that the driver was an ex-Marine who spoke perfect English and the inspector let him through, but in any case, the driver totally broke down both physically and mentally. Moreover, this caused some friction between the higher-ups because they did no work until I got back and straightened things out. No one could find El Gato [the drug smuggler who had done some work with the corrupt U.S. Customs Inspector after hooking up with Ramirez Peyro], and one morning I saw a photo in the newspaper of three guys who had been executed and thrown into a vacant lot and it said they had not been identified.

I went to Bencomo and I told him that I recognized the boots and the shirt one of the guys had on (since you couldn’t see their faces), that it was El Gato Madrid and the other one, judging from his size [corpulence], had to be the architect. And that they went around talking about a crossing with the I.C. After which Bencomo confirmed to me that yes, the third one was an informant nicknamed El Venado, who usually worked for him, but had been passed off to a fellow agent … and they had done a job for them. He also showed me some photos of the bodies, which showed signs of torture, so that I could [not] identify them.

So that’s how I found out that they had brought over a van and one of the thugs’ fathers received it and took it to his ranch, but a helicopter tailed them and the law met them at the ranch, and they even confiscated some new tractors, which they used as “therapy” on the three intermediaries [the murder victims — El Gato; the architect, Miguel Angel Sanches; and the informant El Venado].

FBI Mug shot of Vicente Carrillo FuentesI went on working with the I.C. [the corrupt U.S. Customs Inspector] and all kinds of people joined us and asked that we put them on the list to get their cars across, and they would give them to us already loaded and ready. At the same time, I was getting together with Santillan and my associates and in our conversations everything came out. So one day it came up that that a thug who was said to be Vicente Carrillo Fuentes’s godson, and who in addition to giving us two cars with 1,000 pounds [of dope] each asked that we find him some weapons …. So he gave us a list that supposedly his godfather (Vicente) was looking for from the engineer [Santillan].

Upon hearing that, Santillan became interested and passed the information on to the connection they ordered from that they would interrogate him [the alleged godson], but the guy was picked up by the federal agents and was never seen again. Afterwards, Santillan told me that they had planted drugs on him in one of the interrogation houses.

I asked him what he was going to do with the cars he had from the aforementioned [the thug/godson] and he told me to turn them over to Sadam at the local office, and they would send the marijuana to the northern part of the U.S. and that they would give my associates and me part of the earnings — which I’m still waiting for.

… I told all this to Bencomo in his office as always, according to how things happened. Also around that time, Bencomo told me that if we got a crossing [at the border], I should get a cargo van and that we would attack it [bust it]. And in the end, they were going to take care of it … and that they now had better surveillance equipment.

So I got everything ready and we got the van through to SAEP-850 [an informant] who Bencomo asked me to let drive so he could make a little money since he was broke. This time it was on the Santa Fe Bridge [in Juarez/El Paso].

A little more than halfway across the bridge, the U.S. Customs Inspectors arrived. They handcuffed 850 [the informant] and got into the van. I pretended to be crazy and kept walking with my associate to cross into the U.S. on foot. Thank God my associate as always was such an idiot that he didn’t notice that 850 had been arrested.

As soon as we crossed we walked to Popo’s Bar and I called Bencomo and asked him to explain to me what had happened, to which he replied that there had been a breakdown in communication with the [U.S. Customs] inspectors, but that the bosses were already trying to get 850 and the van released in order to make the “controlled delivery” [finish the sting] but they were not going to be able to take much time to make the seizure. To which I said to him that he should keep it, and that I would talk to him the next day in order to proceed, since I would be calmer then and ready for the big problem that was going to come my way.

The next day we were coordinated and 500 pounds were handed over to some guys who gave me a minivan so that I would give them their cut. They drove about six blocks and they hadn’t finished unloading when the sheriff [in El Paso] caught them.

The other 1,000 pounds I gave to a certain [individual], who took the van, brought it back to me and about thirty minutes later as he was leaving his house, the sheriff and U.S. Customs got him. But they didn’t arrest anyone nor did they give them any [paperwork]. They only took the drugs. In the case of the 500 [pounds] they did arrest about six people. It was so long in coming that it was a major problem for the owners of the drugs and Bencomo gave me false papers and I had to get ready …

To Be Continued

Ramirez’ letter ends in mid-sentence, as though the jailers had just confiscated his pencil, preventing him from finishing his tale.

Ramirez is still sitting in that jail cell, awaiting his fate in the U.S. Justice system — which, based on his prison letter, seems to be quite intertwined with the narco-trafficking world that is waiting to embrace him upon his return to Mexico.

He now exists outside of the fragile fabric of civil society.

In this drug war, he is now the prey.

Stay tuned…

No comments:

Post a Comment