The road to ruin

Once the proud home of America's mighty car industry, Detroit now faces meltdown. Tomorrow, the bosses of Ford, Chrysler and GM will make their final plea for a $25bn government bailout to save their firms, the legacy of Motor City - and nearly 2m jobs. By Ed Pilkington

-

- The Guardian, Wednesday December 3 2008

-

larger | smaller

larger | smaller - Article history

America's automobile industry is badly hit by recession

The Ford plant in Highland Park, a city within the city of Detroit, is a monument to the American automobile. It opened in 1910, and three years later pioneered the world's first car assembly line. In 1925, it spewed out 9,000 Model Ts in a single day. The revolution that turned America into a car-owning democracy had arrived. Today, there is ample evidence of that revolution. The factory looks over a six-lane highway that is heavy with traffic from dawn to dusk. Next door is a drive-thru McDonald's, where customers come to order Big Macs before rolling 50 metres to a drive-thru chemists to pick up indigestion tablets.

The story of the plant is told in one of those green-and-gold heritage plaques erected by the main entrance. It says: "Mass production soon moved from here to all phases of American industry and set the pattern of abundance for 20th-century living." Pattern of abundance: the phrase reads like a sick joke, for the Ford factory it describes is a shell of what it once was. Its red brick and granite walls still stand proud, framed by decorative mosaics. But the windows are broken or boarded up, its ceilings have gaping holes, the floor is covered in broken lumps of fallen plaster. On the roof, the flagpole that for years flew the Stars and Stripes is rusty and bare.

Other companies, other countries, might have turned Henry Ford's factory of dreams into a museum rather than let it decay into the pitiful wreck that it is today. But Ford, and its fellows in the Big Three - General Motors (GM) and Chrysler - have enough to do staying alive without worrying about preserving the past. GM, the giant of the three, has lost $73bn in the past three years; it is haemorrhaging $2bn a month. At that rate it will run out of cash by the middle of next year and collapse by that year's end, potentially bringing millions of workers down with it. Which is why the CEOs of the three giants took their begging bowls to Washington earlier this month, pleading for a "bridging loan" of $25bn.

They didn't get a warm reception. They were ridiculed by senators for having flown in three separate corporate jets, an act that must rank among the most impressive PR disasters of the decade. But what the senators and the largely hostile media coverage missed was that the miserable condition of the Detroit car industry is not merely a comment on the failed leadership of its corporate executives, though it is that. It is also a matter of personal survival for millions of Americans who depend, directly or indirectly, on the revolution Henry Ford began 100 years ago.

Nowhere is this more visible than in Detroit, the crucible of the Big Three. Half of GM's 100,000 workers live in the city, and they in turn support a spider's web of relatives, spin-off industries and services. Detroit is really nothing but a company town. Hamtramckis a city within the city that borders one of GM's main factories. When GM enjoyed good times, Hamtramck boomed. Now GM is in the doldrums, Hamtramck is too. We walk along a stretch of shops along one of its main streets. First in line is Anna's Beauty Salon: it's closed, but the sign on the door suggests Anna is managing to stay open four days a week. Next, Popular Fashion and Variety Store: shut down. Billiards and Burger Hall: abandoned. Antiques store, an oil painting portraying an autumn landscape still in its window: deserted. Law offices: vacant. Funeral home: open. Even in a recession, one aspect of life must go on - the ending of it.

On the other side of the road is the Family Donut shop, a local institution run by a Polish family for the past 28 years. It has a picture of Princess Diana on the wall, a gift from one of the regular clients, and another of the Three Stooges. The owner, Vojno, is unloading a bundle of cardboard boxes used to pack the donuts. A few years ago he would order up to 30 bundles a month; now it's 10. On Polish festive days, there would be a line of customers out the door and round the corner, and the stools at the counter would be loaded. Today, the line is more of a dribble and the counter is largely empty. Unless GM recovers, and money starts flowing again, he will have to close in a few months. "It's not just me. Everybody around here is going to shut down," he says. What will he do if he does have to close? "I'll stay home and sleep. I'm hungry for sleep," he says.

One of the few clients, dressed in a bomber jacket with Detroit written across the back, shouts over at him. "You only work one job, so why do you need to sleep?"

"Shut up, Eddie," Vojno replies.

"I work three jobs to make my money," Eddie Fabiszak says, prompting the only other customer in the bakery to say, under his breath: "Lucky man."

The other customer is Melis Lejlic, 27, a naturalised American originally from Bosnia. His father and mother, two uncles and a cousin all work in the car business. All now fear redundancy. Lejlic works in construction, but that is no better. Car workers are no longer spending on home improvements, so demand for his work has fallen by half. Of 10 builders he knows, seven are unemployed. "Everybody in a small town like this is looking to the car industry, and there's no hope there," he says. "Drive around, you'll see. Detroit is worse right now than Baghdad."

The comparison sounds far-fetched, but in the streets around the GM plant you can see what he means. Several houses have no glazing in their rickety wooden walls. Front lawns have turned into littered pasture. Walls are lined with barbed wire. A mural of a Stars and Stripes has been graffitied. And though it is nothing like Baghdad, there is clearly a market in lawlessness. A poster advertising the services of a lawyer says: "Aggressive criminal defence. Drugs CCW [carrying a concealed weapon] Theft Murder All felonies misdemeanours." That is how Henry Ford's dream looks in November 2008.

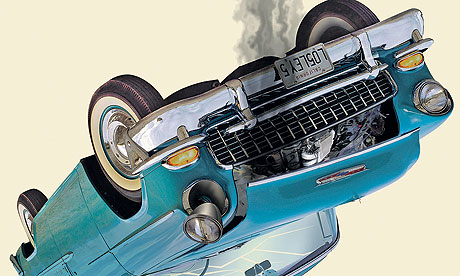

GM's headquarters in downtown Detroit dominate the city's skyline. The seven cylindrical glass towers of the Renaissance Centre were built in 1977 as a statement of the company's untouchable status as the then unquestioned king of the auto world. Inside the main tower, there is an exhibition of some of GM's most memorable models, dating back to the 1950s. It is almost shocking to see how beautiful and exhilarating those cars were. There is a 1953 Chevrolet Corvette Roadster, built largely by hand, its white, sensuous curves set off by red leather seats. Then there's a 1955 Chevrolet Bel Air in black, the quintessential car of the American dream, big enough to carry a family to its suburban home but sufficiently powerful and sleek to avoid any sense of frumpiness. Pride of place goes to a 1959 Cadillac series 62 convertible, which is an outrageously attractive work of art. This was the baby of Harley Earl, GM's legendary designer. Inspired by the tail of a second world war fighter plane, he placed fins on the back of the car, with rear brake lights the shape of rockets and exhausts mimicking those of a jet. The 59 Cadillac summed up an entire generation - young, dangerous, fast, unstoppable.

Peter DeLorenzo spent 22 years working in the car business as an advertising and marketing consultant and now runs an influential website called Autoextremist. He explains that when the explosion of creativity burst out in the 50s, Detroit had just emerged from the crucial role it had played as the manufacturing backbone of the war effort, churning out tanks and missiles at extraordinary rate, and confidence was riding high. "Coming out of the second world war, the automobile was the symbol of American might. GM was the symbol of American might, and most Americans were proud that GM was a successful corporation that turned out magnificent cars people wanted."

The design-led strategy not only generated exquisite cars, it worked handsomely for GM. In 1955, four out of every five cars around the world were US-produced and half of those came from GM. The Big Three monopolised around 95% of the domestic market, and between them they transformed the US. They provided the stimulus for the biggest construction project in world history - the laying of the US interstate highways - and gave birth to the suburbs and to urban sprawl. Think Los Angeles. Think Phoenix rising out of the desert of Arizona.

How you get from the invincibility of those days to the verge of bankruptcy is a cautionary tale for the whole of America as its dominance wanes in an increasingly globalised economy. DeLorenzo, who has written a book called The United States of Toyota, dates the start of the rot to 1979 - just after GM had moved into its monolithic new headquarters in the Renaissance Centre. By then Japanese car companies were already snapping at the heels of the Big Three, but Detroit ignored the threat, steeped in complacency that the good times would last for ever. Leadership within the business also crucially changed hands, from the designers to what DeLorenzo calls the "bean counters".

By the 1990s, the Big Three's reputation for innovation and beauty had withered, replaced by a reputation for faulty products. "People started to associate Detroit with cars coming off the assembly line and their doors falling off," says Micheline Maynard, a New York Times business reporter and author of The End of Detroit: How the Big Three Lost Their Grip. She recounts how in 2002 GM's vice-chairman, Bob Lutz, declared that their vehicles were every bit as reliable as Honda's and Toyota's; that same afternoon GM recalled 1.5m minivans.

From the sleek elegance of the 1959 Cadillac to the lumpen brutality of the Hummer: what was in the mind of the GM executive who conceived putting a machine modelled on armoured vehicles on to the civilian streets of US cities, at barely 13 miles per gallon? But then Lutz has argued that that hybrids like the Toyota Prius "make no economic sense" and once called global warming "a total crock of shit".

The other key element in the demise of Detroit concerns the staple of the American auto industry - the car worker. Ron Nidiffer is drinking beer in the New Dodge Lounge in Hamtramck, temporarily off work as the GM plant has suspended production for want of sales. He has worked in car factories for 36 years, 10 of them on the assembly line. He is one of a dying breed of car workers who had their pay and conditions set back in the heyday. His union, the United Auto Workers, negotiated a series of deals in the 1970s and 80s that have become the albatross around the industry's neck. He makes $29 an hour - substantially more than American workers in Japanese plants that have been transplanted to the non-unionised south, from Alabama to Texas.

But the trouble really starts when you include the so-called "legacy costs", the generous terms agreed for pensions and health care that allowed workers to retire as young as 48. GM now carries about 470,000 retirees and spouses on benefits - more than four times its productive workforce - adding a total of about $2,000 for every car it makes, a terrible burden in the face of fierce foreign competition.

The symbol of excess that the UAW's critics like to point to is the "jobs banks", by which workers are paid 95% of their salaries for doing nothing. The scheme was introduced as a way of ensuring minimum employment levels, but billowed uncontrollably until it included about 40,000 workers. Nidiffer concedes that looking back, the jobs bank was indefensible. "Yes, it was a bad idea. And I understand why some people are jealous of what we've had. We had good conditions, even to excess."

But what annoys him is the assumption that the largesse and complacency that epitomised the attitude of both unions and management is still prevalent today. The job banks have been whittled down to 3,500 workers, and wages have been cut in half for all new employees. He is one of the last at the GM plant in Hamtramck to enjoy the old $29 an hour rate, the others having taken redundancy. A deal has also been struck to lift the burden of legacy costs from GM's shoulders by transferring health insurance into an independent fund administered by the union. After all that, to hear Congress turn away the plea for $25bn from the Big Three CEOs makes Nidiffer see red. "I'm extremely mad. We've made all these concessions, taken the hit, and yet we're still accused of being lazy and greedy."

It has not made him any happier that while Congress rebuffed Detroit, it has bailed out the banks with apparent alacrity, including Citibank which was last week handed the exact amount requested by the Big Three. "We're looking for a pittance compared with what they've given the banks," Nidiffer says. His anger is echoed in the front-page headline in the Detroit Free Press: "$85 billion for AIG. $700 billion for financial firms. $25 billion for Citigroup. Why is the bar so high for $25 billion to Detroit?"

Nidiffer's frustration is heightened by his belief that if Detroit can see it through another 18 months it will have turned the corner. His GM plant is poised to produce the Volt, a new plug-in electric hybrid that will run for 40 miles on one full battery before a tiny petrol motor recharges it. The cutting-edge model, which goes into production in 2010, has been spearheaded by Bob Lutz, the global warming sceptic - a sign of how dramatically the outlook has changed at GM.

But none of the new ideas being scrambled out by the Big Three will matter if they fail to make it to 2010. Will the Volt go down in history as a great idea that GM carried with it to its grave? "There used to be a saying, so goes GM, so goes the country," Nidiffer says. "That was in happy days. But the same is true now. If GM goes under, the ripple effect will be felt throughout America."

A car worker desperate to hold on to his job would say that, wouldn't he? But economists agree. Susan Helper, a professor at Case Western university, says if GM went into bankruptcy next year, it could set in train a knock-on effect that would hit not just the 240,000 employees of the Big Three, but also 730,000 suppliers and about 1 million people working in dealerships across the country. Harder to quantify, but potentially even more devastating, would be the loss of social capital - the knowledge that is imbedded in a generation. "The idea that you can just liquidate Detroit and start again is crazy. Knowledge is not held by any one person, but comes from how people in a company interact."

Crunch time is coming. The tragedy of the American car is approaching its climax. You can feel it, palpably, on the lot of Galeana's Dodge dealership, a short drive away from Nidiffer's watering hole. Balloons in red, white and blue festoon the long line of cars, but who are they fooling? A more accurate reflection of the mood are the signs propped up under a succession of bonnets that spell the word S-A-L-E. Inside, a query about how things are going is met with the reply: "Look at the board." The board in question has just one car handwritten on it - the extent of today's business. Two years ago, the daily average was 15 cars.

Chrysler, which owns the Dodge brand, used to offer huge discounts on the price of the cars disguised as leasing agreements. But in July it announced it was suspending all leasing, and business went through the floor. The Big Three can no longer afford to lower their prices, so instead the cars sit on the lot, looking cheerful beneath the balloons. There is one small cause for hope for Galeana's dealers. A local Chrysler plant has just announced 5,000 job losses, and each worker made redundant will be given a voucher to buy a new Dodge car. It's come to this: the only chink of light for the dealers are the redundancy packages of the workers who make the cars they sell.

This week, the CEOs of the Big Three have one last shot at saving Detroit. They are travelling back to Washington to plead their case again. And this time, they won't be going by private jet - Ford's Alan Mulally will drive a Ford hybrid, and GM chief executive Rick Wagoner and Chrysler CEO Bob Nardelli will fly on commercial planes. Tomorrow and on Friday, they will present Congress committees with a new business plan that is expected to include a cap on top bosses' pay, concessions from the UAW and the death of the most loss-making brands. Less certain is the outcome. Will they get their $25bn and, if they do, will it be anywhere like enough? Or will this once great institution, this embodiment of American might and ingenuity - and with it the livelihood of millions - go the way of Henry Ford's factory of dreams.

No comments:

Post a Comment