How the climate change global editorial project came about

Today 56 major newspapers in 45 countries speak with one voice on climate change ahead of the Copenhagen summit. This is how it happened

-

Climate change poses a particular challenge to journalists. It is almost incontrovertibly the biggest story we cover; perhaps the only one with genuinely existential implications. Otherwise measured scientists discuss it in apocalyptic terms. Campaigners and politicians talk about a crossroads in human history. But how do we reflect the scale and urgency of the issue in the normal register of journalism?

How can it make sense to find a story about the disappearance of arctic sea ice on page 17 of a newspaper, sandwiched between an unexceptional murder trial and the latest bickering over MPs expenses? Or even on the front page, when the same slot the previous day was occupied by a story about plans to trim civil service jobs?

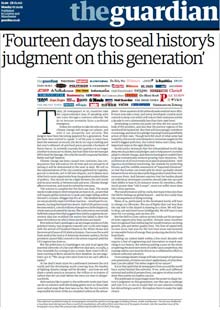

The Guardian's front page on Monday 7 December, with the global editorial.

The Guardian's front page on Monday 7 December, with the global editorial. Hence today's Guardian-led initiative in which 56 major newspapers in 45 countries speak with a single voice (albeit in 20 different languages) through a shared editorial. As Guardian editor-in-chief Alan Rusbridger put it: "Newspapers have never done anything like this before - but they have never had to cover a story like this before."

Aside from trying to provide a wake-up call about the urgency of the emergency facing us, the global leader carries a simple message to the politicians and negotiators gathered in Copenhagen: if all of us who disagree about so much can agree on what must be done, then surely you can too.

Given that newspapers are inherently rivalrous, proud and disputatious, viewing the world through very different national and political prisms, the prospect of getting a sizeable cross-section of them to sign up to a single text on such a momentous and divisive issue seemed like a long shot. But an early, enthusiastic, conversation with the editor of one of India's biggest dailies offered encouragement. Then in Beijing in September, I met a senior editor from an influential business weekly, the Economic Observer.

Notwithstanding the shifting boundaries of press freedom in China, he was sure his paper would participate (and another major Chinese daily would subsequently, too). If we could reach a common position with papers from the two developing world giants most commonly identified as obstacles to a global deal, then surely we could crack the rest.

The Copenhagen climate logo.

The Copenhagen climate logo. Next came Europe, where most of the major titles were quick to sign up to the idea. Among the handful who declined, one influential paper did so on the grounds that the editor of a rival paper already participating in the project had recently said something distinctly uncharitable about its own editor.

A sceptic might point out that it's hardly surprising that European papers can agree on how to act against climate change when the EU has a common negotiating position, but what was more striking was the speed with which the idea began to gather support across the rest of the world - rich and poor.

Each day brought news of some new sublime juxtaposition: Brunei and Canada, Brazil and Botswana, Israel and Lebanon. Among those keen to take part were newspapers in some of the least carbon-hungry nations on earth – Rwanda, Tanzania, Bangladesh – and some of the most: Qatar, Dubai (notwithstanding their little local difficulty), Canada and the US.

Of course, getting papers to agree in principle was the easy bit. The trickier job would be producing a text that everyone could sign up to. After a slightly uncomfortable exchange with an Italian colleague in which I referred to climate change as our "what did you do in the war, daddy?" issue, it was clear that historical analogies were going to be fraught. Out went my favourite Churchill quote: "The era of procrastination, of half-measures, of soothing and baffling expedients, of delays is coming to its close. In its place we are entering a period of consequences."

After a series of discussions with scientists and other experts, we circulated a skeleton argument to the group of papers who had signed up early, and the comments that came pouring back quickly offered a taste of what the real Copenhagen negotiations must be like: our Polish colleagues wanted an acknowledgment that poorer new EU countries should not have to bear as much of the coming burden as 'Old Europe'; our Indian partner suggested that the argument reflected a "lopsided" developed world perspective and needed to say more about what the rich world must do; a Chinese editor wanted to flag the importance of addressing "exported" emissions – those created by the rich world increasingly consuming goods manufactured in developing countries.

Some thought the editorial's assessment of the consequences of inaction was too gloomy; some not gloomy enough. The text went through two more drafts, as our leader writers Tom Clark and Julian Glover sought to reflect each partner's requests without alienating another. Only over one or two specific figures did they abandon the search for consensus: that, I guess, is the difference between hammering out real deals and pontificating about what they should look like. We asked every paper to sign up to the text in its entirety, even if they had to make small cuts for layout purposes, but a sentence acknowledging the controversy over leaked emails from British climate scientists was suggested as an optional add, it being too late to secure everyone's agreement to it.

If the editorial lacks the detail that will have to be cracked over the next 14 days in Copenhagen, it should be a source of encouragement that such a diverse coalition was able to agree about so much - not least the precariousness of our situation, and the need for Copenhagen to deliver a full treaty by summer 2010 at the latest.

Anyone studying the list of newspapers behind the editorial will quickly spot one glaring gap: the absence of any first-rank US paper. A number of major US titles evinced support for the project, even conceding that they agreed with everything in the editorial, but stopped short of signing up, leaving the admirably independent-minded Miami Herald as the sole representative of the world's second biggest polluter. (Next time you're in Florida buy two copies.) It is hard not to be struck by the parallel with the Kyoto agreement when the US stood to one side as the world began to move against climate change.

Another Kyoto holdout is also unrepresented: both the Sydney Morning Herald and Melbourne Age dropped out of the project after climate change convulsed Australian politics, demanding, they felt, a more localised editorial position.

But anyone contemplating the prospects of success in Copenhagen might be cheered that even the newspapers that turned down an invitation to join the project were unerringly supportive of the idea. With one notable exception, that is. One US paper's response: "This is an outrageous attempt to orchestrate media pressure. Go to hell."

What do you want from Copenhagen? Write your own leader.

No comments:

Post a Comment