Société Générale rogue trader to stand trial next year

• Jerome Kerviel accused of causing record €4.9bn losses for French bank

• Trader faces up to five years in prison and €375,000 in fines if convicted

- guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 1 September 2009 09.09 BST

- Article history

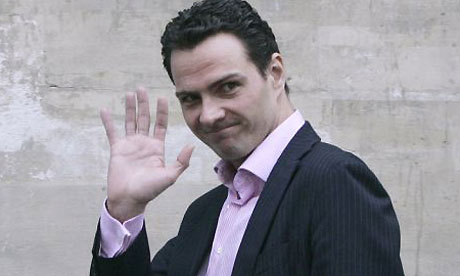

Jerome Kerviel leaving prison in March 2008. Photograph: AP

Former Société Générale trader Jerome Kerviel is to stand trial next year over claims that he cost the bank billions of euros through a series of allegedly rogue transactions.

The bank welcomed the news and has claimed that the junior trader's unauthorised deals caused the record losses of €4.9bn (£4.31bn), which it unveiled last year.

Investigating judges Renaud Van Ruymbeke and Françoise Desset sent the case to a Paris court yesterday, a judicial official said. The trial is expected to start early next year.

Since the losses came to light Kerviel has argued SocGen knew what he was doing, while the bank insists he acted alone.

Jean Veil, lawyer for SocGen, welcomed the decision. Although he had not yet seen the judges' order, he said it appeared that "Société Générale's thesis was confirmed". One of Kerviel's lawyers, Francis Tissot, called the move "regrettable".

The judges threw out a request from prosecutors to send Kerviel's assistant, Thomas Mougard, to trial as well. He was accused of "complicity in introducing fraudulent data in a computer system". Mougard has denied the accusations, arguing he was not aware of the illicit nature of the transactions he was asked to carry out.

Kerviel is charged with forgery, breach of trust and unauthorised computer use, and faces up to five years in prison and €375,000 in fines if convicted. He has admitted building up non-authorised trading positions but has argued his supervisors turned a blind eye while he was making money for the bank, and intervened only when he started to suffer losses.

In January this year, French investigators wrapped up their 12-month probe into €50bn of unauthorised trading positions built up by Kerviel.

At the start of the investigation last year, Kerviel spent six weeks in jail and was then released under judicial supervision. In June, the Paris prosecutor's office requested that Kerviel stand trial, and judges finalised the decision with a formal order yesterday.

The independent investigations and the bank's own internal inquiries into the scandal have found that its managers and control systems failed to operate properly and ignored warnings. A report by PricewaterhouseCoopers blamed the "culture" at the trading desk, describing it as "overheated".

France's central bank has fined SocGen €4m for "serious shortcomings" in its internal controls that led to the trading losses. Kerviel's legal team is trying to go further and prove that the bank knew what was actually happening.

Employed at the bank since 2000, Kerviel worked his way up from a desk that monitors traders to a job on the futures desk, where he invested the bank's money by making huge bets on the future direction of European stock exchange prices.

He is accused of causing five times the financial damage inflicted by Nick Leeson, the rogue trader who sparked the collapse of Barings Bank in 1995 with losses of £800m.

Series of errors allowed Madoff to keep trading

Scathing internal report on investigation by Wall Street watchdog reveals key account was never scrutinised

Thursday, 3 September 2009

REUTERS

Bernard Madoff, who was convicted of fraud in June. The SEC report says he could have been stopped as early as 1992

Bernard Madoff says he thought it was "game over" for his multi-billion dollar fraud in 2006, after he was cornered into handing over details of the empty bank account where he claimed to be holding his investors' money.

But investigators at Wall Street's main watchdog never even looked in the account, and Madoff says he was "astonished" to have remained a free man for another two and a half years.

A searing internal report from Wall Street's top regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission, says that the 2006 failure was just one in a catastrophic series of errors that the agency made in its dealings with Madoff. It could have discovered the fraud and shut him down as early as 1992, but staff were dazzled by his Wall Street credentials and fearful of his power, the report concludes.

At one point Madoff even claimed to be on a short-list to become the next chairman of the SEC.

Over 16 years, the agency received six tip-offs, conducted three examinations and two full investigations, and yet still managed to miss the fact that Madoff had never once made an investment with his clients' money. Cash from new investors was simply going to pay off old ones, and thousands of people who believed their life savings were safe with Madoff were left with nothing when the scheme finally collapsed last December.

In the May 2006 investigation, Madoff testified to SEC staff for several hours, gave evasive and contradictory answers and asked them to accept that his impossibly successful investment returns were the result of his "gut feel" for the stock market.

But it was when they asked for details of the trading account where he claimed to house his clients' investments that he believed they had finally found the key to a fraud that had been getting bigger and bigger for at least 15 years.

"I thought it was the end game, over," Madoff told the SEC's inspector-general. "Monday morning they'll call and this will be over... and it never happened." He "was astonished", he said.

The inspector general has been investigating how the SEC failed to spot the world's largest-ever pyramid scheme, despite repeated warnings from anonymous sources, industry experts and a private investigator who waged a years-long battle to convince them that Madoff's purported trading strategy was impossible. When the SEC did examine Madoff, they concentrated on rumours he was front-running – a stockbroking scam which profits from knowledge of client trading – and failed to follow up clues to a much bigger fraud. In a particularly damaging section of the report, released in summary yesterday, the inspector-general says that the SEC's repeated investigations actually made it easier for Madoff to pursue his crimes. If investors expressed any scepticism about his returns, he told them that the SEC had checked him over.

Madoff was once one of the most powerful men in finance, a former chairman of the Nasdaq stock exchange, whose business had helped introduce revolutionary electronic trading to Wall Street. The SEC, by contrast, put only junior staff on his case, and he was easily able to manipulate them.

"All throughout the examination, Bernard Madoff would drop the names of high-up people in the SEC," one junior examiner said. One senior staff member warned more junior SEC staff to remember that Madoff was "a very well-connected, powerful person".

When the SEC did go to look at the books at the Madoff offices in Midtown Manhattan, he would try to keep members of his staff from talking to the inspectors. When they sought documents Madoff did not wish to provide, he became very angry. One examiner said "veins were popping out of his neck... his voice level got increasingly loud" and he was repeatedly saying: "What are you looking for? Front running. Aren't you looking for front running?"

The SEC had a chance to nip Madoff's fraud in the bud in 1992, when it investigated and shut down a fund management firm that promised implausible "100 per cent" safe investments. The firm was handing all its clients' money to Madoff to invest, but the SEC failed to examine what promises Madoff had been making to the firm.

It was only the market turmoil of last year that finally brought Madoff down, and the full details of his crimes are still not known, despite his guilty plea and his sentencing in June to 150 years in prison. It remains unclear when the fraud began, and how many other people at his firm were involved. Madoff cooperated with the SEC's inspector-general in the investigation of the regulator's failings, but he has not been cooperating with criminal prosecutors.

The inspector-general's report will be published in full in the next few days. Although it excoriates the SEC for incompetence, it does exonerate staff members of having inappropriate financial or personal ties to Madoff. A romantic relationship between Shana Madoff, the fraudster's niece, and an SEC official did not influence the conduct of the SEC's investigations, it says.

Mary Schapiro, who took over as chairman of the SEC in January, said there was no hiding from the fact that the agency missed numerous opportunities to discover the fraud. "It is a failure that we continue to regret, and one that has led us to reform in many ways how we regulate markets and protect investors."

No comments:

Post a Comment